|

October 17, 2016

A DISTINCT CHANGE FOR A DOOARS GARDEN

Click Here to read about the Manabari Greens in Dooars

October 23 2015

We thank Venk Shenoi for forwarding this story by Mark Tully

Mark Tully writes that he would "hate to lose my connection with the great city of Calcutta"

British journalist and former BBC india correspondent Mark Tully explains why he is trying to obtain a copy of his birth certificate from the municipal authorities in Eastern Indian city of Calcutta at the age of 78 I cannot remember when I last needed a birth certificate

how it came about that the place of birth on my passport is Calcutta.

But recently, while applying to be an "Overseas Citizen of India" (OCI), I have found that this is not correct, or may not be correct.

I have been told that Tollygunge, where I was born, was not included within the municipal limits of Calcutta in 1935, the year of my birth.

So I have applied for a copy of my birth certificate to support my application to become an OCI.

Being an OCI allows me to retain my nationality, but I am also issued a lifelong visa for India, allowing me to work and live in the country indefinitely.

I hope I will be allowed to keep my place of birth as Calcutta because I would hate to lose my connection with that great city.

My connection with Calcutta stretches back a long way.

It goes back at least to 1857, the year of what my maternal great-grandfather would have called the Indian Mutiny.

He managed to escape the uprising in eastern Uttar Pradesh in a boat down the Ganges to Calcutta.

My maternal grandfather made his living selling jute in the city. He bought the jute in what is now Bangladesh, which is how my mother happened to be born there.

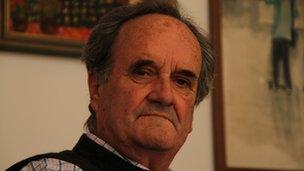

Image captionMark Tully was born in Tollygunge - now a part of Calcutta - in 1935 Image captionMark Tully was born in Tollygunge - now a part of Calcutta - in 1935

But she met and married my father in Calcutta. He was the first of his family to come to India where he became one of the senior partners of Gillanders Arbuthnot, a Calcutta-based firm.

'Politically incorrect'

I remember, too, the kudos being born in Calcutta gave me by making me stand-out as a rarity when, at the age of 10, I found myself in the highly competitive society of a British boarding school.

To boost my kudos even further, I would boast that I was born in the "Second City of the British Empire".

During the nine years that Calcutta was my home, I lived a life which would now be seen as thoroughly politically incorrect.

From our youngest days, we were never allowed to forget that we were different - we were English, not Indian.

We had an English nanny who saw to that. She supervised us 24x7 and once, finding me learning to count from our driver, she cuffed my head, saying "that's the servants' language, not yours".

Inevitably, we were not allowed to play with Indian children. There were even class barriers to the European children we were allowed to play with.

My nanny would not allow us to play with children who only had Indian or Anglo-Indian nannies because their parents couldn't afford a "proper nanny", as she saw herself.

European society in the Calcutta of those days was divided by a strict class system, not dissimilar to the caste system.

Members of the ICS, the Indian Civil Service, were considered the Brahmins (the elite caste), while the members of the Indian army were regarded as the Rajputs (the warrior caste).

As a businessman, my father was a Vaisya (trading caste), dismissed by the snooty ICS and army as a mere "boxwallah".

Image captionMark Tully says he is 'proud of his connection' with Calcutta Image captionMark Tully says he is 'proud of his connection' with Calcutta

'Very proud'

In the 78 years since I was born in what I hope I am still entitled to call Calcutta - not Tollygunge - all this has rightly been swept aside, and my life bears no resemblance to my childhood.

Almost all my friends in India are Indian. I have an Indian son-in-law and an Indian daughter-in-law.

I do know an Indian language, although I would know it a lot better if more people would speak to me in Hindi rather than English.

I am very proud not just of my connection with Calcutta but my connection with India which is approaching 50 years now.

I do not like being called an expat. That's why I do hope to become an Overseas Citizen of India.

That will mean I will be acknowledged as a citizen of the two countries I feel I belong to, India and Britain.

I will bring together the two nationalities which were separated during my childhood.

****************************************************************************************

We have to thank Venk Shenoi for passing this WW1 story to us-

-a great memory of how life was 100 years ago

January 1 2015

The voices of Indian PoWs captured in the first world war

At six o’clock on 31 May 1916, an Indian soldier who had been captured on the Western Front alongside British troops and held in a German PoW camp stepped up to the microphone and began to speak. Not in Hindi or Urdu, Telugu or Marathi but in perfectly clipped English. He tells his audience, a group of German ethnologists, the biblical story of the Prodigal Son. That his voice still survives for us to listen to, clear and crisp through the creak and crackle of time, is an extraordinarily emotive link not just back to the Great War but to the days of Empire.

In The Ghostly Voices of World War One on the BBC’s World Service (produced by Mark Savage) Priyath Liyanage told the story of these soldiers, who fascinated their German captors because of their ‘exotic’ turbans and kurtas. They became objects of study and were let off their labours for the day while the researchers recorded their voices using the latest technology (Edison’s wax-cylinder phonograph). They wanted to study their use of language, their pronunciation. Not just for science. The recordings were also to be used once the war was won (by the Germans, of course) as language training for the officers who would be working to create an even bigger German empire and would need to understand the local dialects.

After the war the recordings were lost, seized by the Russians and taken to Moscow, but eventually they were returned to Berlin where Liyanage went to listen to them in the hope of finding out who the soldiers were and tracing them back to their homes in northern India. It proved a lot more difficult than he anticipated. The recordings were surprisingly methodical, with not just the date but the precise time noted as well as the names of those who were speaking. Photographs, too, were taken. But since many of the soldiers were from tiny villages up in the mountains, very often illiterate and with no tradition of keeping written records, there is little real chance of being able to find their descendants now, 100 years later. When Liyanage travelled to the place where the soldier who talks about the Prodigal Son was supposed to come from, the villagers to whom he played the recording told him, ‘It creates a sense of doubt.’ His English was too good, too well educated

Liyanage, though, persisted. Another of the voices sings devotional songs in Urdu. He plays the recording to an 89-year-old who might well be the singer’s son. The man is visibly moved. He cannot be sure that the voice is that of his father but the song is familiar, and his father was in the army and in France. In a mysterious way he has been given a direct connection with his past. ‘Sometimes,’ he tells us, ‘these moments cannot be defined in words.’

The recordings have also mysteriously survived as another kind of war memorial, reminding us that more than a million Indian soldiers volunteered to fight in Europe in a war with which they had no real connection. Sarfraz Manzoor told their story on Radio 2 on Saturday (in a programme first broadcast on the Asian Network). Forgotten Heroes: The Indian Army in the Great War (produced by Philippa Geering) reminded us that the Indian soldiers arrived in Europe in September 1914, just a few weeks after the declaration of war. It would take months before the British volunteers were ready to fight. The Indians on the other hand were well trained. Some of them would find themselves in Palestine and Mesopotamia fighting against their fellow Muslims, yet they carried on in the most appalling conditions of heat and starvation.

Frank Cottrell Boyce was also asking us to remember these lesser-known voices from the past in his feature for Radio 3 God and the Great War(thoughtfully produced by Rosie Dawson). He set out to unearth stories from 1914–18 that are not usually recalled (or are remembered for the wrong reasons). What about the thousands of teenage girls who were sent up to Gretna Green to work in the highly secret munitions factory, manufacturing cordite by soaking cotton wool in nitroglycerin? It was very dangerous work, they laboured long days and were very young. Off the leash they tended to look for fun, annoying the locals. Yet they were an essential part of the war effort, and fearless.

He looks through the back issues of a parish newsletter created by a Sunday-school teacher in Everton. A soldier reports from the front, one of three brothers, one of whom has just been killed. He writes that he had never understood that text ‘O death, where is thy sting?’ But after being in the trenches, he now realises death is a small thing. ‘It’s all right. It’s just death.’

Out of these individual griefs, says Cottrell Boyce, we build each November ‘a common silence …like a brief, invisible cathedral. If we stand beneath the dome and really listen, we can hear still faintly the echo of their voices.’

**********************************************************

February 9 2014

Thanks to Venk Shenoi for forwarding this to the Editor. It shown on the BBC on January 24 2014 and the Editor thought it would be of interest and educational to Tea People

How Vietnam became a coffee giant

By Chris Summers BBC News

By Chris Summers BBC News

Think of coffee and you will probably think of Brazil, Colombia, or maybe Ethiopia. But the world's second largest exporter today is Vietnam. How did its market share jump from 0.1% to 20% in just 30 years, and how has this rapid change affected the country?

When the Vietnam war ended in 1975 the country was on its knees, and economic policies copied from the Soviet union did nothing to help.

Collectivising agriculture proved to be a disaster, so in 1986 the Communist Party carried out a U-turn - placing a big bet, at the same time, on coffee.

Coffee production then grew by 20%-30% every year in the 1990s. The industry now employs about 2.6 million people, with beans grown on half a million smallholdings of two to three acres each.

This has helped transform the Vietnamese economy. In 1994 some 60% of Vietnamese lived under the poverty line, now less than 10% do.

Coffee Vietnamese style

- Ca phe da - Coffee served on a bed of ice

- Ca phe sua da - Coffee served with condensed milk, on ice

- Ca phe trung - like a cappuccino, except with the addition of an egg or two

- Kopi luwak - The process of making coffee by feeding beans to civets - a type of weasel - and then roasting the excreted beans

"The Vietnamese traditionally drank tea, like the Chinese, and still do," says Vietnam-based coffee consultant Will Frith.

Vietnamese people do drink it - sometimes with condensed milk, or in a cappuccino made with egg - but it's mainly grown as an export crop.

Coffee was introduced to Vietnam by the French in the 19th Century and a processing plant manufacturing instant coffee was functioning by 1950.

This is how most Vietnamese coffee is consumed, and is partly why about a quarter of coffee drunk in the UK comes from Vietnam.

British consumers still drink a lot more of that than of fancy coffees, such as espressos, lattes and cappuccinos.

High-end coffee shops mainly buy Arabica coffee beans, whereas Vietnam grows the hardier Robusta bean.

Arabica beans contain between 1% to 1.5% caffeine while Robusta has between 1.6% to 2.7% caffeine, making it taste more bitter.

There is a lot more to coffee, though, than caffeine.

"Complex flavour chemistry works to make up the flavours inherent in coffee," says Frith.

"Caffeine is such a small percentage of total content, especially compared to other alkaloids, that it has a very minute effect on flavour."

Some companies, like Nestle, have processing plants in Vietnam, which roast the beans and pack it.

But Thomas Copple, an economist at the International Coffee Organization in London, says most is exported as green beans and then processed elsewhere, in Germany for example.

While large numbers of Vietnamese have made a living from coffee, a few have become very rich. Dang Le Nguyen Vu: Next step, an international coffee shop chain

Take for example multi-millionaire Dang Le Nguyen Vu. His company, Trung Nguyen Corporation, is based in Ho Chi Minh City - formerly Saigon - but his wealth is based in the Central Highlands around Buon Ma Thuot, the country's coffee capital.

Chairman Vu, as he is nicknamed, owns five Bentleys and 10 Ferraris and Forbes magazine assessed him to be worth $100m (£60m). That's in a country where the average annual income is $1,300 (£790).

Who buys Vietnam's coffee

- Vietnam produced 22m 60kg bags of coffee in 2012/13

- Germany and the US imported about 2m

- Spain, Italy and Belgium/Luxembourg imported about 1.2m

- Japan, South Korea, Poland, France and the UK all imported in the region of 0.5m

The expansion of coffee has also had downsides, however.

Agricultural activity of any kind holds hidden dangers in Vietnam, because of the huge numbers of unexploded ordnance remaining in the ground after the Vietnam War. In one province, Quang Tri, 83% of fields are thought to contain bombs.

Environmentalists also warn that catastrophe is looming. WWF estimates that 40,000 square miles of forest have been cut down since 1973, some of it for coffee farms, and experts say much of the land used for coffee cultivation is steadily being exhausted.

Vietnamese farmers are using too much water and fertiliser, says Dr Dave D'Haeze, a Belgian soil expert.

"There's this traditional belief that you need to do that and nobody has really been trained on how to produce coffee," he says.

Hanoi has independent coffee shops - last year it got its first Starbucks

"Every farmer in Vietnam is the researcher of his own plot."

Some people from Vietnam's many ethnic minorities also say they have been forced off their land.

But Chairman Vu says coffee has been good for Vietnam.

He is now planning to set up an international chain of Vietnamese-style coffee shops.

"We want to bring Vietnamese coffee culture to the world. It isn't going to be easy but in the next year we want to compete with the big brands like Starbucks," he says.

"If we can take on and win over the US market we can conquer the whole world."

*****************************************************************************************

July 24, 2013

QINGHAI TIBET RAILWAY

We are most grateful to Venk Shenoi for sharing theis great collection with us

This is a wonderful collection of photos of the railway on the roof of the world

It is 47 pics. It is a Power Point Presentation and takes a while to download but worth the time. Click Here to see the slide show.

|